Anonymous Authors & Altered Manuscripts: What We Know About the Bible

Textual criticism of the Bible has been a discipline for over 300 years, focused on examining existing manuscripts to reconstruct the original text. However, the findings of these studies largely stay within academic circles, leaving most Christians unaware. Hans Conzelmann, Professor of New Testament Studies at Tottingen, has acknowledged this issue: “The Christian community continues to exist because the conclusions of the critical study of the Bible are largely withheld from them.”

This article outlines the key findings from New Testament experts :

- The four gospels were written by anonymous authors, and the names Luke, Mark, Matthew, and John were attributed to them much later.

- All New Testament books were written in Greek by anonymous authors who were highly proficient in the language, while Jesus himself spoke Aramaic.

- None of the Gospel authors were direct eyewitnesses to the life of Jesus.

- The authors of the Gospels did not aim to write a biography of Jesus; instead, they sought to present a portrayal of him that reflected their theological beliefs and perspectives.

- There is no documented evidence supporting an oral tradition for the transmission of the Gospels.

- A gap of over 170 years exists between Jesus’s ascension in 30 AD and the earliest surviving manuscript longer than two pages, which dates to approximately 200 AD.

- We only have copies of copies of the original texts, and there is no certainty about who copied from whom.

- Most of the manuscripts we have today originate from the Middle Ages rather than the early Christian centuries.

- These manuscripts differ significantly, with an estimated over 200,000 variations among them.

- The manuscripts exhibit both intentional and unintentional alterations, some of which directly influence Christian beliefs.

Who wrote the gospels, what the gospels are and what they are not

Christians believe that the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) were written by those whose names appear in the titles of the books. Most also believe they were written in the same order as in the Bible.

The truth is that all the author’s names are pure conjecture or pious fraud. The titles “According to Matthew,” etc., were only added at the end of the second century. All four gospels were originally anonymous, none claims to have been written by eyewitnesses, and all contain clues that they were written several generations after Jesus by well-educated Greek-speaking theologians, not illiterate Aramaic speakers.

The Gospels are written by unknown Greek-speaking authors

Who authored the Gospels of Mark, Luke, Matthew, and John? For two centuries, New Testament scholars have largely agreed that the authors’ identities remain unknown. However, the tradition within the Christian Church holds that these texts were written either by Jesus’ apostles or by individuals closely associated with them.

- Gospel of Matthew: attributed to the apostle Matthew.

- Gospel according to John: Attributed to the apostle John.

- Gospel of Luke: Attributed to Luke, companion of Paul of Tarsus.

- Gospel of Mark: Attributed to Mark, companion of Matthew.

Bart D. Ehrman is a professor specializing in the history of religion in the United States and the author of many works on Christian literature. In his book Forged: Writing in God’s Name—Why the Authors of the Bible Are Not Who We Think They Are, Ehrman discusses the true identities of the Bible’s authors.

Other writings are “anonymous,” literally, “having no name.” These are books whose authors never identify themselves. That is, technically speaking, true of one-third of the New Testament books. None of the Gospels tells us the name of its author.

Only later did Christians call them Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; and later scribes then added these names to the book titles. Also anonymous are the book of Acts and the letters known as 1, 2, and 3 John. Technically speaking, the same is true of the book of Hebrews; the author never mentions his name, even if he wants you to assume he’s Paul.1

Forged: Writing in the Name of God-Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They ArBart Ehrman

Although Jesus and his apostles spoke Aramaic, these texts were composed in Greek.

Whereas the Old Testament was written mostly in Hebrew, with some portions in Aramaic, the New Testament was, apart from a few individual words (e.g. Mark 5:41, 7: 34, 15: 34//Matt. 27: 46), written virtually entirely in a form of ancient Greek. This much has long been recognized by scholars and others alike.

Porter, Stanley E. (2006). « Language and Translation of the New Testament

The Gospels are not eyewitness accounts

The language used in the gospel texts implies that none of the authors witnessed the events they describe. The dating of the Gospels supports this idea: Paul’s letters were written much earlier than the Gospels, and Paul himself was not an eyewitness.

Since the four gospels — Matthew , Mark, Luke , and John — Begin the New Testament readers often assume that these works were the earliest written products of the Christian church .

This assumption is often coupled with the beliefs that the authors of the four gospels were eyewitnesses of the events they narrate and that the composition of the gospels was a relatively simple process of preserving in writing what they had seen and heard firsthand. Such assumption about the Gospels, however are inaccurate.

All the letters of Paul in the New Testament were written prior to any of the Gospels being completed. The authors of the gospels or at least the person responsible for the final form of the gospels were almost certainly not eyewitnesses; and the Gospels themselves are the end products of traditions that were transmitted and preserved in various forms, both oral and written.

Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels Page 13

The Gospels represent theologically interpreted narratives rather than reliable historical testimonies.

We believe God sent a book called “The Gospel” to Jesus Christ, which He then shared with His apostles and the Jewish people through His teachings. However, what we call the “Gospels” today are pretty different. They are biographies of Jesus’s life, accompanied by some sayings attributed to Him. It’s important to note that these are not modern biographies but rather ancient ones :

Since the 1970s, however, the question of the Gospels’ genre has come under increasingly close scrutiny, and it has become much clearer that the Gospels are in fact very similar in type to ancient biographies (Greek bioi; Latin vitae). That is, their interest was not the modern one of analysing the subject’s inner life and tracing how an individual’s character developed over time. Rather, the ancient view was that character was fixed and unchanging; and the biographer’s concern was to portray the chosen subject’s character by narrating his words and deeds.

Which is just what we find in the Synoptic (in- deed all the canonical) Gospels, though not, it should be noted, in the other Gospels now frequently drawn into the neo-Liberal quest. Moreover, it is clear that common purposes of ancient bioi were to provide examples for their readers to emulate, to give information about their subject, to preserve his memory, and to defend and promote his reputation. Here again the Gospels fit the broad genre remarkably well. Of course, it remains true that the Gospels were never simply biographical; they were propaganda; they were kerygma. But then neither were ancient biographies wholly dispassionate and objective (any more than modern biographies).

Dunn, James D.G. (2005). « The Tradition ». In Dunn, James D.G.; McKnight, Scot (eds.). The Historical Jesus in Recent Research. Eisenbrauns. ISBN978-1575061009.

The Gospels are not objective narratives; instead, they are narratives designed to defend a particular dogma and a specific vision of Jesus.

The Gospel writers were not interested in simply writing down all the traditions about Jesus they could find. Rather their task was to present to their readers a specific interpretation of who Jesus was. Their works are not “objective” historical accounts (no account is ever bias-free), but rather are narratives shaped to reveal particular understandings of Jesus.

The Gospels are theological works as much as or more than they are historical works. The evangelists selected from the traditions available to them the stories and teachings of Jesus that were compatible with their understandings of him. They often reshaped and retold these traditions in order to highlight or downplay certain aspects of the life and teachings of Jesus. The Gospels then can best be understood as theologically interpreted history.

An Introduction to The Gospels Mitchell G. Reddish

Michel Reddish confirms this observation by providing an example from the Gospel According to Luke:

Thus even though the Gospel writers may have written what they supposed to be historically accurate, there is no guarantee that the events or details described by the evangelists are in actuality historically correct.

Perhaps an example from one of the Gospels would help clarify this point. In the Gospel of Luke, the author describes the birth of Jesus as occurring in connection with a census that was taken “while Quirinius was governor of Syria” (2:2).

Elsewhere Luke implies that Jesus was born during the reign of Herod the Great or, at the latest, within a year after his death.’ Herod died in 4 BCE; Quirinius was not governor or legate of Syria until 6 CE Obviously Jesus could not have been born during the reign of Herod (which the Gospel of Matthew explicitly says) and during the rule of Quirinius.

Luke presented this information as historical fact. Luke likely supposed that the information was historically accurate. Luke’s intention to present his- torical information, however, was thwarted by faulty data .

An Introduction to The Gospels De Mitchell G. Reddish

In the absence of oral or written tradition, the Gospels are dated according to their content

We don’t know who the evangelists are, let alone what they look like. In his book Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament(Pag 44) bruce metezger states: “By comparing with Hellenic representations of ancient Greek poets and philosophers, it appears that Christian artists, who had no knowledge of the evangelists’ portraits, adopted and adapted familiar portraits of pagan authors in contemporary art.D’après les recherches de A. M. Friend, Jr, tous les premiers portraits chrétiens des évangélistes remontent à deux séries principales de quatre portraits chacune : l’une concernait les quatre philosophes Platon, Aristote, Zénon et Épicure et l’autre les quatre dramaturges Euripide, Sophocle, Aristophane et Ménandre. »

The importance of a transmission chain

Hadiths are sayings attributed to the prophet Muhammed(ﷺ), and they have been transmitted by written and oral tradition. The main difference between hadiths and the gospels is that as far as hadiths are concerned, we know who collected them, who transmitted them, and who made the original statement that was transmitted.

So, for example, person A said something, then person B heard it, and he decided to pass it on and tell other people C-D-E, then they passed it on to others, and so on. Basically, all along the chain of hadith transmission, we know who’s who, we know who’s transmitting the story, and we know where the original story came from. There’s a complete line of transmission.

This is crucial because it means that the reports are not anonymous, that they come from people we know, names and people we can identify, we know where they lived, when they were born, when they died, etc. Again, this is very important because if you know the person, you also see whether they are reliable or unreliable; for example, someone reporting the Hadith, a person in the chain, could have been known as a liar, as someone unreliable, someone who would make things up, and so we see whether they are passing or recounting a Hadith that we can question the authenticity of.

Vice versa, the person narrating the Hadith may also be known as a truthful person, a reliable person, etc., and therefore, we know that the Hadith he passes is dependent, or it is very likely that it is dependent.

The absence of a chain of transmission of the Gospels

In the case of the Gospels, we have none of this, we literally don’t know who was passing on the stories, they’re all anonymous. Even the supposed collectors Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John were not Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John! The Gospel stories are all anonymous written accounts-collected by people-authors we don’t really know, and they tell stories-incidents of people we don’t know either, the whole chain of transmission in the Gospels is unknown and anonymous.

Basically, in the Gospel story, we have the source, Jesus, then we have the people A-B-C-D-E who pass on the stories-teachings of Jesus, but we have no idea who these sources A-B-C-D-E are, whether they are reliable people and so on, we know nothing about them literally. The only person we know of whose life we have some idea of (through his own writings) is Paul of Tarsus, and yet he barely wrote a few words about the words and life teachings of Jesus, and curiously enough, in his own writings, we can see that he was at odds with the true followers of Jesus.

So when it comes to the Gospel of Mark, and we read all these stories and sayings about Jesus (pbuh), we’re reading stories that were passed down by people we don’t know, and they were collected in a book called Mark by an author we don’t know either, although there’s a lot of speculation about who the exact author is. On the other hand, when it comes to hadiths, when we read a story about the Prophet Muhammad(ﷺ) , we know exactly who passed on the story and who told it; we have a complete line of transmission of who heard it said, and who passed on the saying, and to whom it was passed on, and we know whether these people are solid people or not.

All this is obviously crucial, let’s give an example, let’s say you’ve heard a news report, and it announces some really great news but there’s no source, you’re probably not going to believe it’s true? Especially in this day and age when there are all kinds of sites on the Internet that sometimes report crazy stories, which then turn out to be false, but most of the time, you yourself know to doubt and not believe certain news coming from certain organizations-websites because you know they’re not reliable.

And you also know the organizations-websites-people who are reliable, so you can trust what they say because you know who they are etc. So it’s very important to know your source, if you don’t know your source then as you can see, you’re in big trouble.

Now, taking the same simple logic and applying it to the Gospels and Hadiths (for some strange reason, people often don’t like to use this simple logic, acting as if we’re dealing with another field), it’s important to know our sources, who we’re dealing with, who’s passing on the story, whether the person passing on the information is a reliable or unreliable person.

The Gospels are dated according to their content

Given that there is no oral tradition of transmission of the Gospels and that no manuscript worthy of the name exists before two centuries after Jesus Christ), New Testament specialists rely mainly on textual analysis to define the dates on which the Gospels were written. The style of the text and the events cited make it possible to give an approximate date for the writing of these Gospels, but this dating remains speculative and does not cancel out the fact that we are dealing with anonymous writings transmitted by anonymous people for mainly dogmatic reasons.

The Synoptic Gospels

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are called the Synoptic Gospels because they contain the same stories, often in a similar order and in similar or sometimes identical terms. They contrast with the Gospel according to John, whose content is largely different.

The Gospel according to Mark

He portrays Jesus as a man of heroic deeds, an exorcist, a healer and a miracle-worker. He is also the Son of God, but keeps his messianic nature a secret, even his disciples don’t understand.

Mark’s Gospel was traditionally placed second, and sometimes fourth, in the Christian canon, as an inferior abridgment of what was considered the more important Gospel, Matthew. The Church has consequently drawn its vision of Jesus primarily from Matthew, secondarily from John, and only remotely from Mark, a vision that has changed following the latest in-depth studies and textual analyses of the New Testament:

Opinion on Mark’s value underwent a radical shift in the first half of the 19th century when, on the basis of careful internal investigations of the rst three Gospels, scholars 4 hypothesized that Mark was not a slavish follower of Matthew but rather the earliest of the Gospels, and a primary source for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.

The Gospel according to Marc James R.Edwards

Most scholars date Mark to c. 66-74 AD, shortly before or after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD. They reject the traditional attribution to Mark the Evangelist, the companion of the apostle Peter, which probably arose from the desire of early Christians to link the work to an authoritative figure. Instead, they consider the Gospel to be the work of an author working with a variety of sources, including collections of miracle stories, controversial stories, parables and a passionate narrative.

Mark was probably the first gospel to be written, scholars have long thought it was produced around 35 or 40 years after Jesus’ death, around 65 or 70 AD

Bart Ehrman Jesus, Interrupted: Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (And Why We Don’t Know About Them)

The Gospel of Matthew

Most scholars believe that the Gospel of Matthew was composed between 80 and 90 AD, with a range of possibilities between 70 and 110 AD; a date earlier than 70 remains a minority opinion. The work does not identify its author, and the early tradition attributing it to the apostle Matthew is rejected by modern scholars. He was probably a Jew, standing on the margin between traditional and non-traditional Jewish values, and familiar with the technical legal aspects of the scriptures debated in his day.

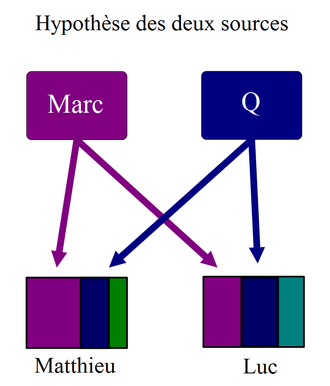

Writing in a polite Semitic “Greek synagogue,” he drew on Mark’s Gospel as his source, as well as the hypothetical collection of sayings known as Source Q (material shared with Luke but not with Mark) and material unique to his own community, called Source M or “Special Matthew.”

Early Christian tradition, first attested by Papias of Hierapolis (c. 125-150 AD), attributes the Gospel to the apostle Matthew, but modern scholars reject this.

Early in the history of the church, the view arose that the first Gospel in the canon was written by Matthew, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus and an eyewitness of his ministry. Most scholars doubt this tradition, pri- marily because the author relies on a number of earlier sources.

This is true whether one accepts the two-document hypothesis or a more com- plex theory. It seems unlikely that an eyewitness of Jesus’ ministry, such as the apostle Matthew, would need to rely on others for information about it.

Another tradition also refers to Matthew as an author, but does not seem to be speaking about the Gospel of Matthew as we have it.About 140 CE, Papias, bishop of Hierapolis, wrote : “Matthew compiled the sayings in the Hebrew dialect, and each person translated them as he was able.” (QUOTED IN EUSEBIUS, ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY 3.29.16) .

.An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity ( page 174) Delbert Burkett

Here Papias describes a work written in Hebrew (or Aramaic), while Matthew is written in Greek and does not appear to be a translation of a Semitic Gospel. Thus if Matthew did write such a work, it was not the Gospel that now carries his name.

Gospel according to Luke and the Book of Acts

Like the other Gospels, the Gospel according to Luke makes no reference to its author, although it does begin with a prologue by the author, explaining that he is reporting what he heard:

Inasmuch as many have taken in hand to set in order a narrative of those things which have been fulfilled among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having had perfect understanding of all things from the very first, to write to you an orderly account, most excellent Theophilus,

Luke 1.1-4

The author of the Gospel according to Luke is probably the same author of the book of Acts. The traditional view that it was Luke the Evangelist, Paul’s companion, is still sometimes advanced, but the consensus among scholars is that the many contradictions between Acts and the authentic Pauline letters.

The most probable date for its composition is around 80-110 A.D., and there is evidence that it was still being revised as late as the 2nd century.

The Gospel, according to John

Christian tradition has attributed it to one of Jesus’ disciples, the apostle John, son of Zebedee. This hypothesis is today rejected by most historians, who see in this text the work of a “Johannine community”, at the end of the 1st century, whose proximity to the events is debated.

In ancient times, as nowadays, an author always speaks in his own name when describing events he has seen; yet in the Gospel according to John, it does not appear that the author himself has seen what he is talking about. Furthermore, in the 21st chapter of this Gospel (V. 24), we read: “This is the disciple who testifies of these things, and wrote these things, and we know that his testimony is true.” . Here, we refer to John in the third person, after which the writer speaks on his behalf. “We know that” shows that the writer is someone other than John himself. It is likely that the writer found notes from John and followed them in composing his account.

We start from the fact that the Fourth Gospel has always been known as the Gospel according to John, and this goes with the traditional view that the evangelist was the apostle John. Although this tradition continues to have supporters among modern scholars, the majority cling to it only in the most tenuous form, or abandon it altogether. It is thus important to see the reasons why the traditional identification is regarded by most scholars as untenable.

Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John M. (2000). The Johannine Literature Page 41

The Gospel of John, like all the gospels, is anonymous.John 21:22 references a disciple whom Jesus loved and John 21:24–25 says: “This is the disciple who is testifying to these things and has written them, and we know that his testimony is true”.

Early Christian tradition, first found in Irenaeus (c. 130 – c. 202 AD), identified this disciple with John the Apostle, but most scholars have abandoned this hypothesis or hold it only tenuously; there are multiple reasons for this conclusion, including, for example, the fact that the gospel is written in good Greek and displays sophisticated theology, and is therefore unlikely to have been the work of a simple fisherman.

Rather, these verses imply that the core of the gospel relies on the testimony (perhaps written) of the “disciple who is testifying”, as collected, preserved, and reshaped by a community of followers (the “we” of the passage), and that a single follower (the “I”) rearranged this material and perhaps added the final chapter and other passages to produce the final gospel.

Wikipedia Gospel of Jean

In his book, The Gospel According to John (I-XII), pp. xxxiv- xxxvi, Father Raymond E. Brown, a world authority on Johannine literature, postulates five stages in the composition of the Gospel:

- Stage 1: The existence of a body of oral tradition independent of the synoptic tradition.

- Step 2: Over a period of up to several decades, traditional material was sifted, selected, and shaped into the form and style of the individual stories and speeches that formed part of the Fourth Gospel.

- Step 3: The evangelist organized the collected material and published it as a separate work.

- Step 4: The evangelist republished his Gospel to meet the objections or difficulties of several groups.

- Stage 5: A final edition or redaction by someone other than the evangelist, whom we’ll call the editor.

What do we know about the transmission of the New Testament?

The myth of the original texts

Greek scholar David Alan Black mentions two factors that make textual criticism of the New Testament necessary:

(1) the originals have disappeared, and (2) there are differences in the copies that remain [David Alan Black, “Textual Criticism of the New Testament” in Foundations for Biblical Interpretation].

In the mind of the ordinary Christian, the texts of the New Testament are a unique redaction from “original texts” existing since the first centuries. However, these “original texts” do not exist. What does exist are the transcriptions that appeared between the 4th and 10th centuries. Bart D. Ehrman is a professor of the history of religion in the USA and the author of numerous works on Christian literature. In 2005, he wrote a book entitled: “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why”:

Not only do we not have the originals, we don't have the first copies of the originals. We don't even have copies of the copies of the originals, or copies of the copies of the copies of the originals. What we have are copies made later — much later. In most instances, they are copies made many centuries later. And these copies all differ from one another, in many thousands of places. As we will see later in this book, these copies differ from one another in so many places that we don't even know how many differences there are. Possibly it is easiest to put it in comparative terms: there are more differences among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament.Misquoting Jesus Bart D. Ehrman page 10

Two centuries between Jesus and the first manuscript, Complete

Almost all the apologetic books that preach the good news of the authenticity of the New Testament mention that we possess more than 5700 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament. But omit to say that, apart from 4 small fragments that I will present in the rest of the article, the first true manuscripts date from 200 AD, i.e. more than 170 years after the rise of Jesus, Joachim Kahl, graduate in theology from Phillips University in Marburg, declares :

The ignorance of most Christians is largely due to the lack of information provided by theologians and ecclesiastical historians, who know two ways of concealing the scandalous facts in their books. Either they distort reality into its exact opposite, or they conceal it.”

JOACHIM KAHL, The Misery of Christianity, Harmondsworth, 1971.

Modern scholars have concluded that the canonical Gospels passed through four stages in their formation:

- The first stage was oral and included various stories about Jesus, such as the healing of the sick or the debate with opponents, as well as parables and teachings.

- In the second stage, oral traditions began to be written down in collections (collections of miracles, collections of sayings, etc.), while oral traditions continued to circulate.

- In the third stage, early Christians began to combine written collections and oral traditions in what might be called “proto-gospels” – hence Luke’s reference to the existence of “many” earlier accounts of Jesus.

- In the fourth stage, the authors of our four Gospels drew on these proto-gospels, these collections, and the oral traditions that were still circulating to produce the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

In his book “Die Religion des modernen Menschen (The Religion of Modern Men)”, Dr. Robert Kehl (1914-2001) states:

Most believers in the Bible have the naive credo that the Bible has always existed in the form in which they read it today. They believe that the Bible has always contained all the sections which are found in their personal copy of the Bible.

`They do not know and most of them do not want to know that for about 200 years the first Christians had no “scripture” apart from the Old Testament, and that even the Old Testament canon had not been definitely established in the days of the early Christians, that written versions of the New Testament came into being quite slowly, that for a long time no one dreamed of considering the New Testament writings as Holy Scripture, that with the passage of time the custom arose of reading these writings to the congregations, but that even then no one dreamed of treating them as Holy Scriptures with the same status as the Old Testament, that this idea first occurred to people when the different factions in Christianity were fighting each other and they felt the need to be able to back themselves up with something binding, that in this way people only began to regard these writings as Holy Scripture about 200 AD!

Robert Kehl Die Religion des modernen Menschen (The Religion of Modern Men)

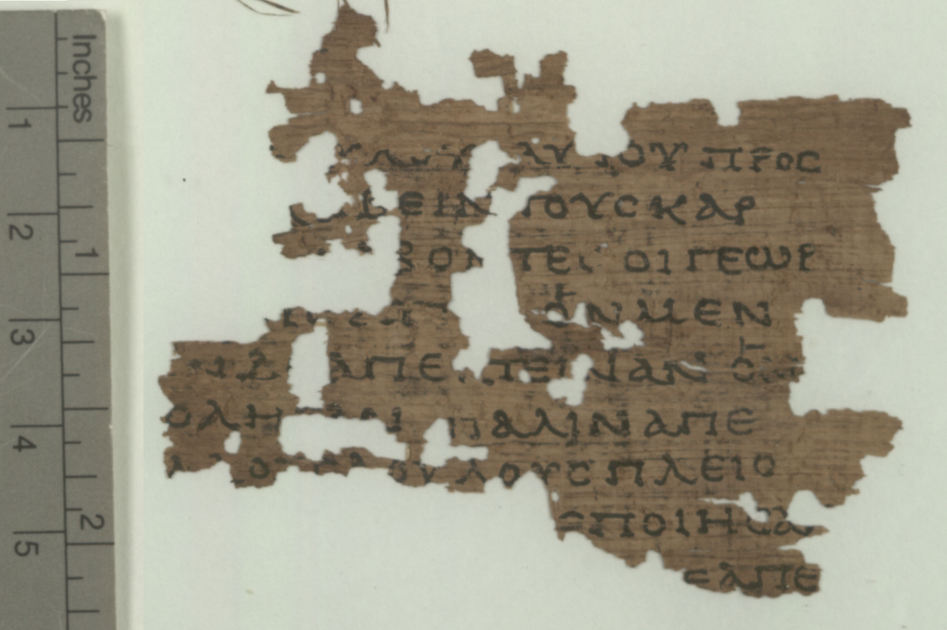

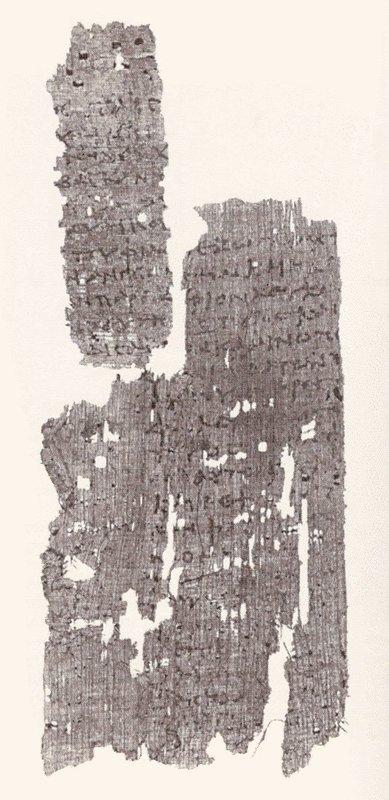

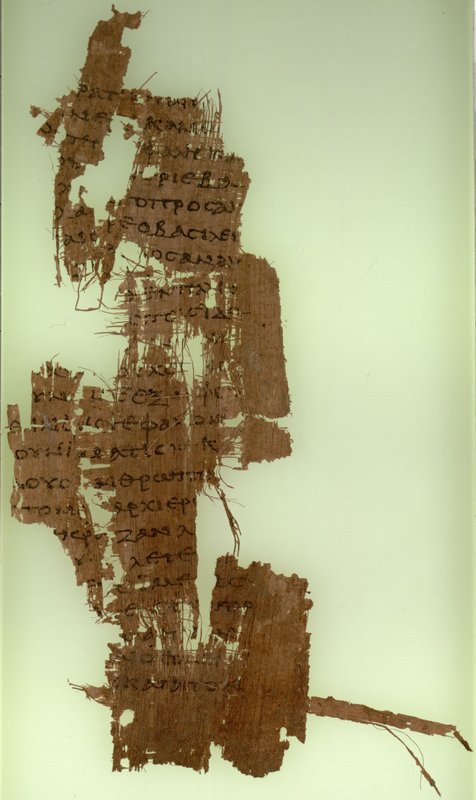

Fragments of the second century

As mentioned above, it wasn’t until the year 200 that we began to see manuscripts that gave us an idea of the text, such as the famous Papyrus 66, P 66, which contains almost all of John’s gospel (but not the story of the adulterer).

Here are the fragments we have from before the year 200:

New Testament manuscripts

From papyrus to parchment

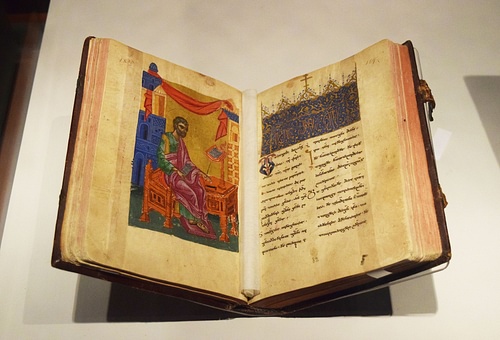

Greek manuscripts fall into different categories, depending on their medium or type of writing. They are divided into four classes: papyrus, uncials, minuscules, and lectionaries.

Papyrus

Papyrus manuscripts, made from reed pith and organized in the form of scrolls, so named because of the writing material used, number around 88 and are generally the oldest manuscripts. Unfortunately, they also tend to be fragmentary and sometimes in poor condition, as papyrus is highly perishable.

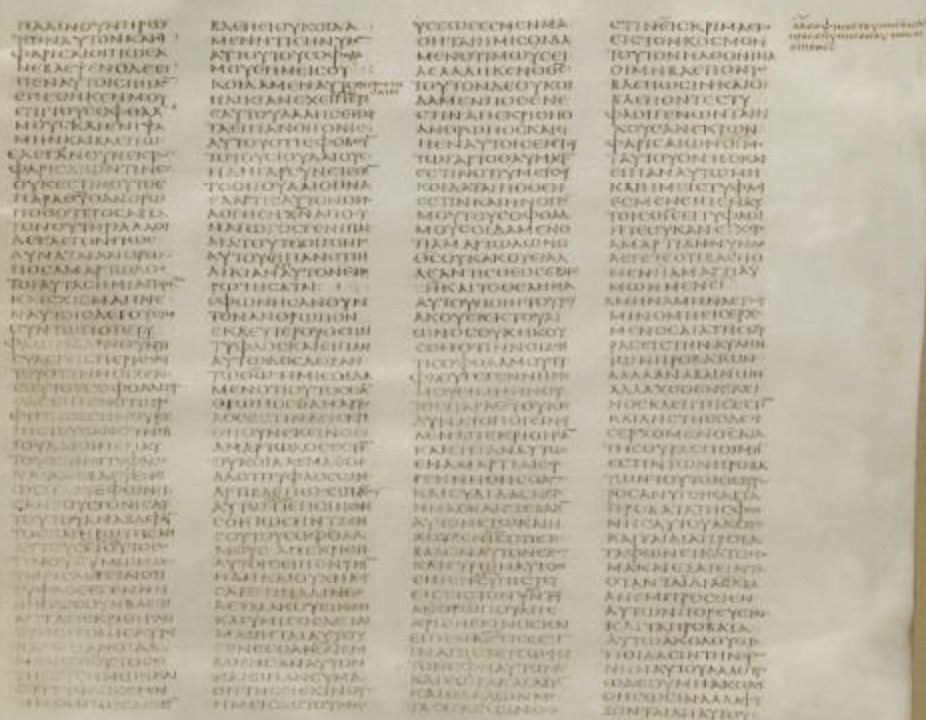

Uncials

Uncials are manuscripts written on parchment, made from calfskin or sheepskin, and organized in separate sheets. It was around the beginning of the fourth century CE that it began to take the place of papyrus in the manufacture of the best books, and works deemed worthy of preservation were gradually transferred from the papyrus scroll to the parchment codex. written in a type of script comparable to our capital letters. This type of writing is square in shape and is a slow and laborious way of copying a document. However, this form of writing flourished until the ninth century. Uncial manuscripts are generally written on vellum or parchment. There are some 274 such manuscripts in existence.

The Codex Sinaiticus is one of the most famous and almost complete manuscripts of the New Testament. is available on this website.

In this image of John 9.35, we can see another example of the deliberate alteration of the Bible. In John 9.35, Jesus says to a man: “Do you believe in the Son of God? In the codex Sinaiticus, Jesus says: “Do you believe in the Son of Man? , Son of man, which is the original reading, has been replaced by “Son of God.”

Minuscules

Minuscules are manuscripts written in a cursive style. Much faster to copy, this style of writing eventually replaced the uncial script. Around 2,800 of these manuscripts exist on vellum or parchment, but they are later than the uncials.

List of minuscules in the New Testament

Lectionaries

Lectionaries are a special type of manuscript designed for the public reading of the Scriptures. Numbering over 2,200, lectionaries use both uncial and minuscule script. Although lectionaries generally date from the sixth to twelfth centuries, they are generally good manuscripts because they were copied for public use in churches.

List of New Testament lectionaries

The New Testament manuscripts: thousands of manuscripts, but …

Today, we can say that there are thousands of New Testament manuscripts: Bruce Mezeger has counted 5735 New Testament manuscripts ( Metzeger The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration).

While this figure is indeed large and impressive, does it truly validate the Church’s assertion that it faithfully retains the precise words of the New Testament authors? According to Michael W. Holmes, the consistent response provided by defenders is “misleading” because :

This bare statement does not reveal the circumstance that approximately eighty-five percent of those manuscripts were copied in the eleventh century or later, over a millennium after the writing of the New Testament. With regard to the fifteen percent or so of manuscripts that do date from the first millennium of the text’s existence, the closer one gets in time of the origins of the New Testament, the more scarce the manuscript evidence becomes. Indeed, for the first century or more after its composition, from roughly the late first century to the beginning of the third, we have very little manuscript evidence for any of the New Testament documents, and for some books the gap extends toward two centuries or more.

In The Reliability of the New Testament: Bart Ehrman and Daniel B. Wallace in Dialogue (ed. by Robert Stewart; Fortress, 2011) 61-79.

Manuscript dates

Very few manuscripts of New Testament writings date from the first three centuries of the Christian era. For this reason, William L. Petersen has determined that :

To be brutally frank, we know next to nothing about the shape of the ‘autograph’ gospels; indeed, it is questionable if one can even speak of such a thing. […] the text in our critical editions today is actually a text which dates from no earlier tha[n] about 180 CE, at the earliest. Our critical editions do not present us with the text that was current in 150, 120 or 100 much less in 80 CE.

See William. L. Petersen, “The Genesis of the Gospels,” in A. Denaux, ed. New Testament Textual Criticism and Exegesis, BETL 161, Leuven: Peeters and University of Leuven Press, 2002, p.62

The difference between the manuscripts and today’s bible: evidence of bible alteration

Divergent manuscripts

With around 6,000 Greek manuscripts of various parts of the New Testament, there are estimated to be around 200,000 variant readings if we count each variant each time it occurs.

B. B. Warfield, professor of didactic and polemical theology at Princeton Theological Seminary from 1887 to 1921, painted an equally bleak picture. He noted that each copy of a manuscript

Was made laboriously and erroneously from a previous one, perpetuating its errors, old and new, and introducing still newer ones of its own manufacture. A long line of ancestry gradually grows up behind each copy in such circumstances, and the race gradually but inevitably degenerates, until, after a thousand years or so, the number of fixed errors becomes considerable.

Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield, An Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament (New York: Thomas Whittaker, 1889) 14.

Many manuscripts, however, bear the traces of numerous corrections made by later scribes and users of the manuscript. Gordon Fee observes that :

They also know that no two of the 5340-plus Greek MSS of the NT are exactly alike. In fact the closest relationships between any two MSS in existence-even among the ma- jority-average from six to ten variants per chapter. It is obvious there- fore that no MS has escaped corruption.

Gordon D. Fee, “Modern Textual Criticism and the Revival of the Textus Receptus” JETS 21:1 (March 1978): 23

Sample Manuscripts

After the 4th century, several codices written on animal skins were found. These manuscripts generally contain the majority of the New Testament but show clear divergences on several points:

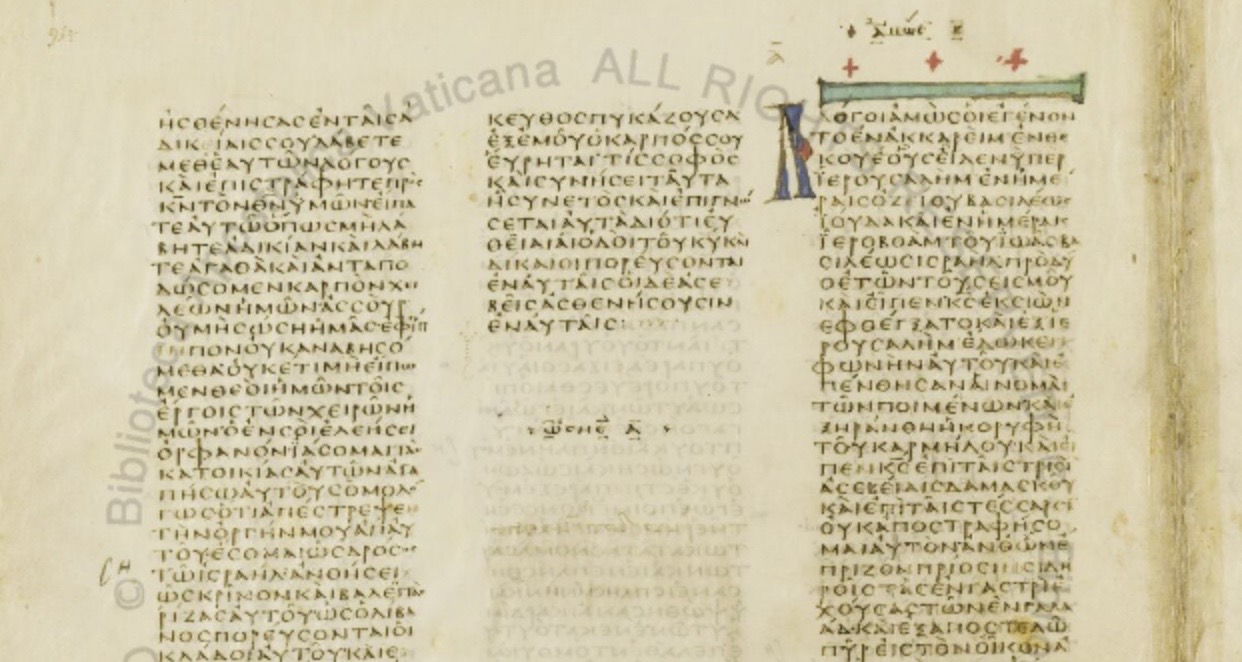

- Codex Vaticanus: dates from the 4th century and includes the Old and New Testaments

- Codex Sinaiticus consists of the Old and New Testaments

- Codex Alexandrinus: 5th century

- Codex Ephraemi: 5th century.

- Codex Bezae: 5th century

Codex Sinaiticus, discovered by Constantinus Tischendorf and believed to date back to the 4th century, is regarded as one of the most remarkable manuscripts of the Bible. Wikipedia says it is “one of the two oldest manuscripts (along with the Codex Vaticanus) that includes the entire biblical canon as we know it today.” This makes it a vital piece in the evolution of the biblical text Christianity.

However, Tischendorf, who discovered it in 1844 in a library in the convent of St. Catherine in Sinai, claims to have found over 16,000 corrections attributed to seven different copyist-translators. Some passages were even erased three times, only to be replaced a fourth time by entirely different texts. (Synopse, Huke Lutzmann)

2. Codex Bezai: 5th century, F.H.A Scrivener counted 15 correctors, 9 in the Greek part and the rest changed the Latin part (FHA Scrivener, Six Lectures on the text of the New Testament and the ancient MSS).

3. Codex Ephraimus: analysis has shown that it was altered at least twice: the first 251 changes, the second 272 changes; moreover, it owes its title “Ephraim” to a person named Ephraim who erased most of the Assyrian text and wrote the Greek translation over it (FHA Scrivener, Six Lectures).

4 Codex Claromontanus: In the 6th century, F.H.A. Scrivener recorded more than 2,000 critical changes. (F.H.A. Scrivener, Six Lectures)

Codex Sinaiticus , fin marc début Luc, on peut noter l’absence de la célèbre fin Marc (16.9-20) ,cette fin n’existe pas non plus dans les autres anciens manuscrits comme le codex Vaticanus, nombreux commentateurs pensent que ce passage n’existe pas dans le texte original et qu’il fut ajouté ultérieurement .